by Sofie Bates

The order of arrival determines which invasive grasses predominate, according to a combination of experiments and computational modeling. The results could help in efforts to preserve the native plants that remain.

Rolling golden hills are an iconic landscape in California, but these golden grasses aren't native to the Golden State. As invasive European grasses swept through California, their numbers quickly surpassed that of native species.

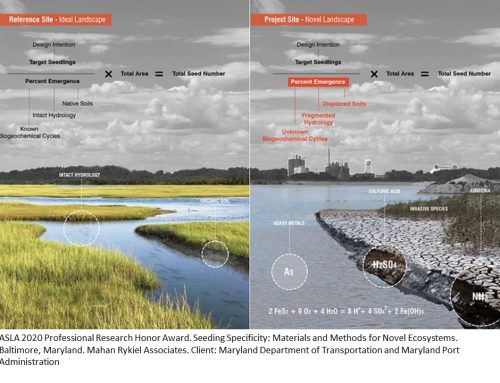

Stanford researchers monitor plant growth at Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve to learn about native and invasive species. (Image credit: L.A. Cicero)

Although California's grasslands are yellow with invasive species, some native bunch grasses survived. The question is how best to protect those that remain. To find answers, Erin Mordecai, assistant professor of biology at Stanford University, turned to grasslands near campus to understand how native and invasive grasses compete.

"We're interested in the plants and animals of California because it's an unusually diverse place," Mordecai said. "A lot of these species only occur here, which is why it's important to protect them."

Mordecai and her research team monitored plant growth in plots at Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve, located in the foothills near Stanford campus, and extrapolated into the future with computational models. The team found that invasive species generally outcompeted native ones, and the first invaders tended to dominate the landscape. The study was published January 10 in The American Naturalist.