Explore how Olmsted shaped Stanford University in California.

by Cathy Blake

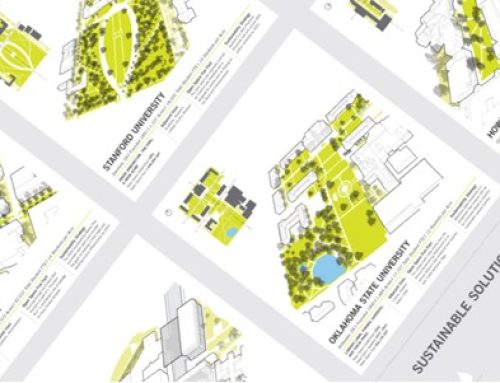

Stanford University (Job No. 01032) is located in California’s Silicon Valley and is intricately intertwined with its history. When railroad magnate and former California Governor Leland Stanford and his wife Jane lost their only child, Leland, Jr., to typhoid, they decided to build a university as the most fitting memorial. They endowed the University with a fortune including their 8,180-acre Palo Alto stock farm, then traveled to seek counsel from Presidents at Harvard, MIT and Cornell –resulting in the hiring of Frederick Law Olmsted.

Leland Stanford Junior University was founded in 1885, “to promote the public welfare by exercising an influence on behalf of humanity and civilization.” In 1886, Frederick Law Olmsted arrived at the Farm to begin planning the physical campus. Although Stanford had commissioned Olmsted to create the design, their relationship was contentious. Whether it was selecting the site, creating quadrangles more reminiscent of California missions than the English countryside, or determining the orientation of the Church and entry drive, Stanford was involved in every major decision. The result was a campus master plan of extraordinary ambition with a built-in negotiation between industry and nature.

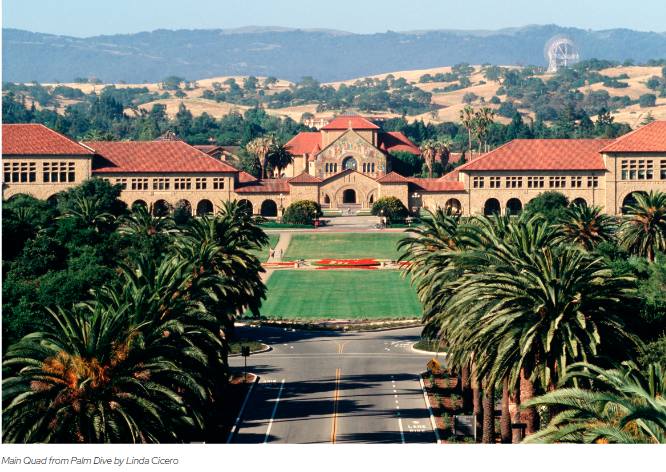

The master plan is distinctive for its monumental scale and use of sight lines. Olmsted established Palm Drive as the central axis and iconic approach extending south from Leland’s railroad station through open space, now Stanford’s Arboretum. The arrival sequence culminates in an Oval centered on the entrance to the main quadrangle with views to foothills beyond. This juxtaposition of a formal monumental series of experiences embedded in a larger natural context was often repeated in later Olmsted projects. The east-west repetition of quads with housing on the diagonals accommodates growth.

Following the 1891 opening, there were many challenges to the Olmsted Plan including two major earthquakes, the addition of buildings in the Beaux Arts period that blocked the axes of the Olmsted design, and efforts by Modernist landscape architects including Thomas Church and Lawrence Halprin to break up the formality of the design. Further interventions came from zealous engineers accommodating the automobile with major streets and parking lots throughout the campus. Rapid addition of new buildings after World War II and phenomenal institutional growth brought the plan to a critical breaking point.

In 1989, the Stanford trustees asked campus planners, “Where are we going?” This resulted in the Second Century Plan which reaffirmed the Olmsted Plan and embodied principles being implemented today. Differences include the “taming” of the automobile by incorporating a Campus Drive loop road and moving parking out of the core, and expansion of the single band of academic quads to multiple rows giving the university greater flexibility.

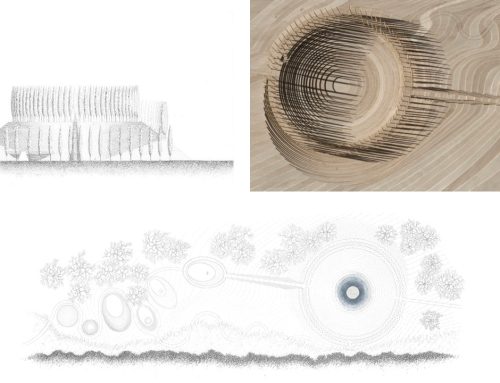

Restoration and redevelopment continue as Stanford implements its master plan. The Science and Engineering Quad (SEQ), for example, advances Olmsted’s plan for interlocking quadrangles to the east and west of the main quad. The 8.2-acre SEQ reinterprets the main quad and restores an original east-west sight line. The loop road and major malls have been established and reconnected.

Beyond the physical, principles important to Stanford and Olmsted are also preserved. The campus was to be inclusive, “nonsectarian, co-educational and affordable, to produce cultured and useful graduates, and to teach both the traditional liberal arts and the technology and engineering.” Housing for faculty and students –important to Olmsted and Stanford– remains important today. The campus was always transit-oriented, focused on the railroad. Today, the axis and grids also integrate very active shuttle, bike and pedestrian travel.

Olmsted based the landscape design on plants appropriate to the semi-arid climate with limited water resources. He favored natural beauty and color over annuals and decoration. These principles are fundamental to today’s campus landscape. As Olmsted wanted, lawns are limited; and those that now exist are irrigated with non-potable water. The architecture incorporates sustainable principles including exterior circulation, arcaded walkways, buildings that form spaces, and large trees with shade to cool the outdoor environment. Landscape connective elements unite the campus and native oak drifts connect to larger campus open spaces. Read the article on olmsted200.org.