by April Philips

Landscape architects must look at the hidden connections between climate adaptation, urban agriculture, food waste, community equity, and public health. By applying systems thinking that integrates climate adaptation and carbon drawdown strategies with foodshed planning, the industry can advance innovative solutions to address these critical issues facing our urban communities.

There is a distinct advantage for designers and planners in gaining a deeper understanding of how climate positive solutions build greater community resiliency, why systems thinking is key to solving the climate crisis, and why addressing the food landscape matters in shaping a more equitable and healthier, more nourished world.

The Intersection of Food + Climate + Resilient Communities

Food and climate are intricately entwined, and human health—the health of you and everyone you know and everyone on this planet—is impacted by this intricate dance. Every single person on the planet needs to eat to live, to nourish our bodies, to grow. We all are affected by the climate we live in. Our food is affected by the climate it grows in. Food becomes the platform from which we can connect with both each other and the land. How might we commit to nourishing both?

“The garden suggests there might be a place where we can meet nature halfway.”

– Michael Pollan

Shift from 3,000 square-foot to 10,000 square-foot edible garden – walking the talk. For the VF Outdoor Headquarters in Alameda, the edible garden went from 3,000 sq ft to 10,000 sq ft to walk the talk on health and environmental company values. / image: Designing Urban Agriculture, by April Philips

Michael Pollan has said that we can meet nature halfway in our gardens. Isn’t this sustainable thinking? We eat food and hopefully it is nourishing food. We know that climate change is an existential threat impacting cities and countries globally, but did you know that 1 in 9 Americans struggle with hunger on a daily basis? Before the pandemic, 14 percent of Americans were experiencing food insecurity—40 million people were unsure where they’d find their next meal. According to Feeding America, this number in 2020-2021 has risen to 17 percent or 54 million people who are now food insecure. Until we are back to normal, the signs show this number will continue to rise.

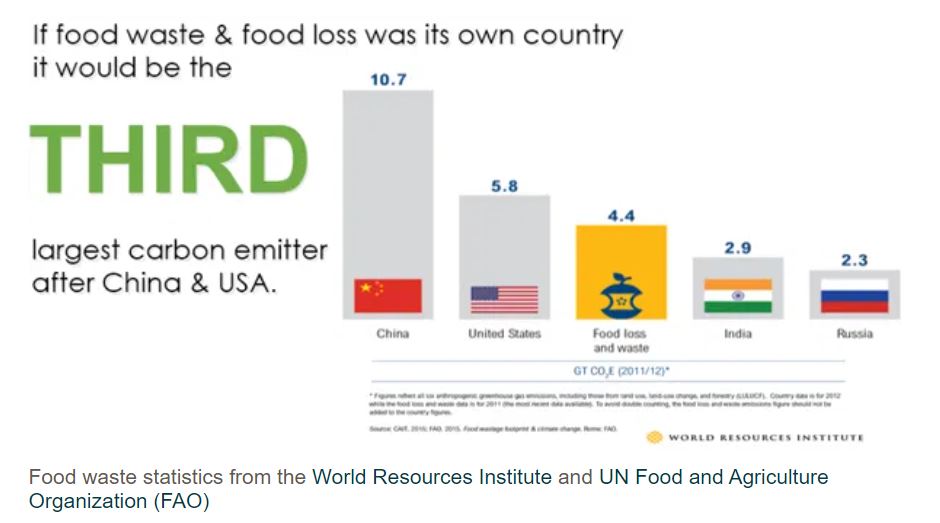

The saddest thing about hunger in the US and around the world is that we globally produce enough food to feed 10 billion people but one-third of all the food produced is wasted. The world wastes 3 billion pounds of food annually which is enough to feed 3 billion people. In the United States, about 30-40 percent of all food bought is not eaten. If food waste was a country, it would be the THIRD largest carbon emitter after China (number 1) and the United States (number 2).

Statistics from the World Resources Institute indicate that 805 million people go hungry every year; when you do the math, since we already produce enough food to feed 10 billion people, it is within our reach to solve this problem if we can find solutions to eliminate food waste.

Let’s reframe the issue: in addition to air and water, food is a basic human need and provides a new perspective for answering the question, “How do we make our cities and regions more livable places in the face of climate change?”

Access to local, healthy food and fresh water, and designing communities adaptive to climate change create positive externalities that benefit people and the planet. Food is a “gateway drug” to fostering sustainability and resilient communities.

We can no longer think Reduce, Reuse, Recycle—we now need to think Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, and Recover.

Systems Thinking is Key to Solving Climate Issues

John Muir famously wrote, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” One lesson nature teaches us is that everything in the world is connected to other things. Systems thinking presents a different lens through which to understand the complexity of the world and in creating a sustainable city where the food system and living systems are part of the green infrastructure.

There is an urgent need to rethink our urban systems as connected to our ecological systems. Linking food to our urban environments is a critical starting point to envisioning more resilient cities and communities. Foodsheds can be mapped just as watersheds are mapped to document performance. The current dilemma with explaining food as an infrastructure system within the city seems to be limited by our inability as a society to think of food in this manner.

Cities tend to view urban agriculture as a temporary activity, not a permanent one.

Rethinking our urban systems as connected to ecological systems / image: Designing Urban Agriculture, by April Philips

Ecological Design and Foodshed Planning

Foodshed planning is still considered to be in its infancy. Farms have been rapidly disappearing over the past few decades. There has been a growing movement to use Land Trusts to help protect them and keep them from being destroyed. And, even though the urban agriculture food movement is associated with young people, over 80% of our farmers are actually over 60 years of age. If we don’t take action to address local food and climate issues, who is going to feed us?

Agrihoods, a planned development integrated with agriculture such as The Cannery in Davis, CA, and Serenbe in Fulton County, GA, promote a more idealistic but healthier farm to table lifestyle. These projects and others represent a relatively new planning model. Many others are aiming to redefine this new development strategy.

Sustainable farming is now being reframed as “regenerative” agriculture which does indicate that we need a new vocabulary to broaden the dialogue on healthy food, healthy planet. The term “regenerative” describes processes that restore, renew, or revitalize their own sources of energy and materials. Regenerative design seeks to not merely lessen the harm of new development, but rather to put design and construction to work as positive forces that repair natural and human systems. This strategy is a climate adaptive solution.

Carbon farming, or sequestering carbon into the soil, is an important part of regenerative farming. The highly inspirational film Kiss the Ground (currently on Netflix) explains in very plain and succinct language how healthy soil is important for both more nutrient dense food as well as a climate adaptive solution in drawing down carbon from the atmosphere. Landscape performance, building healthy soils, creating habitat for pollinators, and increasing biodiversity are just some ecological design principles that define ecological systems thinking.

Cities in California including San Diego, Los Angeles, and San Francisco have developed sustainable farming initiatives and policies that include education on carbon farming as part of their Climate Action Plans and climate initiatives.

There is a critical need for an ecological agriculture system with minimal fossil fuel inputs to be integrated into our new sustainable city models and green infrastructure frameworks. Healthy soils enrich the soil web, promote water conservation, eliminate erosion, and are the foundation for resilient landscapes—urban or rural.

Drawdown / Drawing Down Carbon from the Atmosphere

We have a carbon problem. Rising carbon equals rising temperatures. The challenge, as outlined in the book Drawdown, edited by Paul Hawken and published in 2017, is that we have to remove 10 gigatons a year of green house gases (GHG)—roughly equivalent to 150 Hoover Dams—to keep the temperatures from rising any more. The opportunity, as outlined in Drawdown, is that we already have 100 of the most substantive solutions to reverse global warming and to start reducing the 59% gap between the man-made outputs and the natural carbon sinks of our planet.

The book points out where we can reduce our carbon emitting sources, how we can support our carbon sinks for sequestration, and how we can improve society through tackling this huge climate issue head on. “Food issues represent 8 of the top 20 growth solutions in drawing carbon down from the atmosphere,” according to Jonathan Foley, Executive Director of Project Drawdown. From a strictly urban design and planning lens, other solutions designers should continue to leverage for drawing down carbon include: walkable cities (#54), composting (#60), green roofs (#73), solar roofs (#10), perennial biomass (#51), and using biochar (#72).

Landscape architects also have a new carbon footprint calculator called Pathfinder. The Pathfinder tool is an app created by the Climate Positive Challenge that calculates the carbon footprint of the materials in a project in order to guide designers to reach the target years to positive. The tool works by calculating the lifetime embodied carbon, operational carbon, and sequestered carbon of any project. It is based on the principle that the sooner the project can offset its emissions, the greater its impact on extracting carbon from the atmosphere is.

The process involves research into the Environmental Product Declarations of materials, understanding what components of the products we use are harmful and what part of the process emits the most CO2, and then substituting these products with low carbon emission alternatives.

In a recent project, our studio imputed into the calculator for the AIM Center for Food & Agriculture and Marin Farmers Market master plan to demonstrate how many years to positive can vary with the project’s specific material choices. The material substitutions studied for one synopsis report concentrated on the paved areas, which have the maximum emission potential the project would need to mitigate. With every substitution in these options we are able to calculate the impact of the project and turn it from a socially conscious project to an environmentally conscious one as well. Other sustainable strategies will also come to play as the project is further realized over time and choices are weighed against multiple factors and goals to meet the mission and vision set by the client, farmers, and community stakeholders.

The AIM Center for Food and Agriculture scenarios include a carbon footprint that ranges from 2 years to positive to 15 years to positive depending on material selection choices. / image: April Philips Design Works, Inc.

Carbon Reduction Design Tools

The answer for designers and planners is that we need to advance climate adaptive solutions that also drawdown green house gases and promote resilience if we want to achieve resilient communities.

There are tools available for landscape architects to help shape climate and food policy and to advance carbon drawdown from the atmosphere, sustainable agriculture, and zero waste. There are also climate adaptive solution tools that help to look at ecosystem services and landscape performance to create more climate responsive and resilient landscapes that will be more adaptive to the rising climate threats facing us today.

- Climate Positive Design Challenge and the Pathfinder tool

- Project Drawdown’s Climate Solutions 101

- The Landscape Architecture Foundation’s Landscape Performance Series

- The Sustainable SITES Initiative® (SITES®), developing sustainable landscapes

- Feeding America to learn about food insecurity in your state

- Zero Waste Home and other apps in your city/state

Designer as Change Agent: Designing for Integration

As designers and planners we need to think of ourselves as change agents and participate at all levels of engagement, not just by designing but by taking a more active role in our local communities to advance systems thinking and establish a sustainable food system model. My belief is that we all need to become more active engaged citizens of the world. I hope that more landscape architects, urban designers, planners, and ecologists will play a more public role in the future to lead these initiatives and keep them moving forward.

April Philips, PLA, FASLA, is Principal of April Philips Design Works, Inc. April is a design thought leader, creative systems thinker, author, artist, and unique problem solver. She has an extensive background in a broad range of projects throughout the United States, Pacific Rim, and Middle East that have involved design coordination with multidisciplinary design teams for both public and private sector clients. April was honored by the American Society of Landscape Architects as a fellow in 2010. She has a Bachelor of Landscape Architecture from Louisiana State University, and is licensed in multiple states.